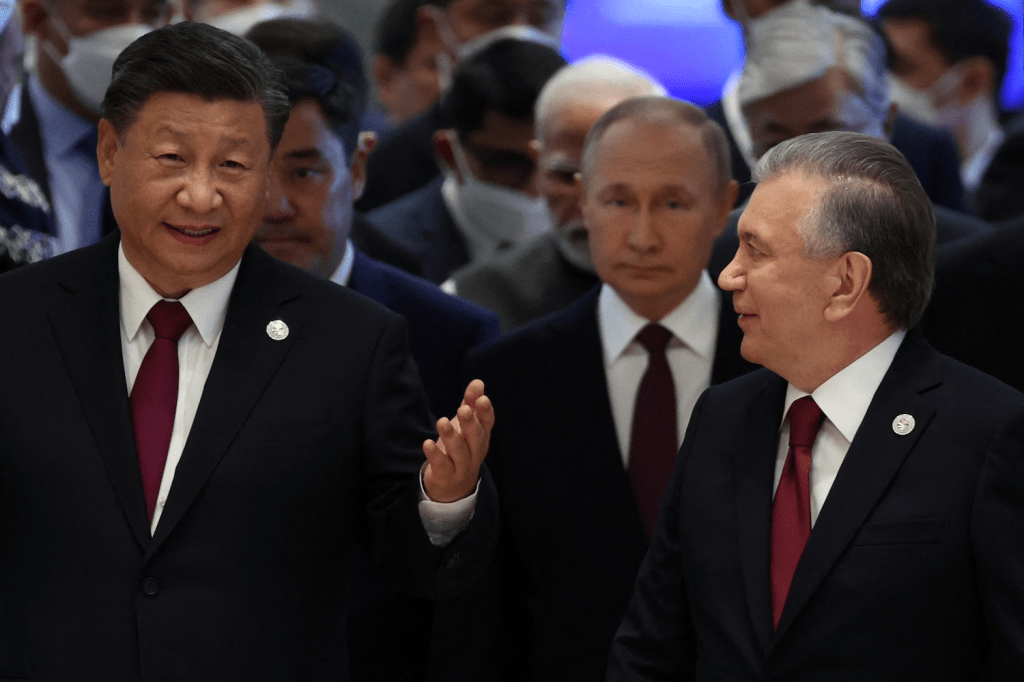

Last week Xi Jinping chaired the inaugural ‘China-Central Asia Summit’. The five autocratic leaders of the ‘C5’ (Kazakstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) travelled to Xi’an, the starting point of the ancient Silk Road, to discuss energy, trade, education, and regional security.

With Russia and the US both drained by costly and unpopular wars in Ukraine and Afghanistan, Xi took the opportunity in his opening address, to pitch China as the regions new security guarantor. Having both your trade and security dominated by one superpower neighbour, is historically never a very popular proposal, but with no one else at the auction, it may well be an offer the C5 cannot afford to refuse.

All the states attending last weeks summit were once firmly in the orbit of the Soviet Union. After its collapse Russia retained the role of security guarantor for the regions strongmen, who required protection against the threat of ‘colour revolutions,’ popular discontent and each other. However, since China’s economic ascendency, the region has enjoyed a ‘multi-vector’ set of political and economic relationships with its superpower neighbours.

Mainly kickstarted by the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013, the PRC became the area’s dominant investor and trading partner, and during the mid 10’s a balance formed, Russia handling the regions security, China handling business. This has been largely favourable to all parties, allowing the Central Asian nations to avoid creating dependencies on any-one of the big powers, and allowing Russia and China to share the resource burden their roles require of them.

However, last year Russia threw a Ukraine shaped spanner in the works. Today, with the Red Army barely moving, the regions confidence in Russia’s ability to guarantee its security is falling apart. No serious material shifts in trade or bi-lateral agreements have occurred yet, but key players in the C5 are making their anxiety and discontent heard. In outright protest of Russia’s “beligerency” in Ukraine, Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, recently refused to recognise the annexation of Donetsk and Luhansk at the Saint Petersburg International Economic Forum.

With this context weighing heavy on all attendees of last weeks summit, Xi looked to put China in pole position to fill the vacuum a Russian retreat from central Asia might cause. The summit’s official communique heralded the meeting as bringing the China – Central Asian relationship into a “new era”, where security would be a central pillar:

- “It is important to safeguard peace in the region. China is ready to help Central Asian countries strengthen capacity building on law enforcement, security and defense, support their independent efforts to safeguard regional security and fight terrorism, and work with them to promote cyber-security. The countries will continue to leverage the role of the coordination mechanism among Afghanistan’s neighbours, and jointly promote peace and reconstruction in Afghanistan”

Although there is no specific mention of Russia in the document, committing to “coordinating” efforts to reconstruct Afghanistan, and describing China as standing “ready” to strengthen and support the [Central Asian nations] efforts to “safeguard regional security” make his ambitions to play a greater role in governing the security relationships in the region pretty transparent. Besides, for a man as famously cryptic as Xi, this is about as blunt as it gets.

This is the latest and boldest move Xi has made towards progressing his ‘Global Security Initiative.’ Launched late last year, it is as big as his Belt and Road program in scope, and aims to challenge the western democratic security order of treaties and international organisations led by the US.

For this reason, developments in Xi’an will significantly spike the red scare in Washington. But with building hostility towards Biden’s investment in Ukraine at home, as well as a recent chaotic withdrawal from a deeply unpopular war in Afghanistan, the US simply cannot afford to go toe to toe with China in this part of the world, as it once did with Russia. The money and public support simply isn’t there. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, in a visit to Astana in early March announced $25 million to “diversify trade” in the region. Pocket change, when compared to the $3.7 billion China announced a month later.

History, geopolitics and time, are all pointing towards a central Asia dominated by China. This is not what central Asian states will want, and it is certainly not the future Russia wants. They will resist this for as long as they can, and depending on how the war in Ukraine pans out, the status quo could hold for longer than expected. But the damage to the Russian economy, Putin’s reputation and most importantly his military, has made this a question of when, not if.